“Food is not fuel. It is not nutrition. It is fun, educational, horizon expanding, delightful. It is consoling, transporting and a comfort. If you want a happy eater, run a happy kitchen. These things take time, but so do all good things.â€

— Laurie Colwin, “More Home Cooking: A Writer Returns to the Kitchen,†(1993)

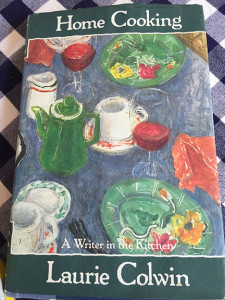

“[N]o one who cooks cooks alone,†wrote Laurie Colwin in her collection of food memoir essays, “Home Cooking: A Writer in the Kitchen.†“Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers.†Among Colwin’s favorite cppkbook authors were Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson, Edna Lewis and the contributors to an eclectic Southern collection from the Charleston, SC, Junior League called, “The Charleston Receipts.â€

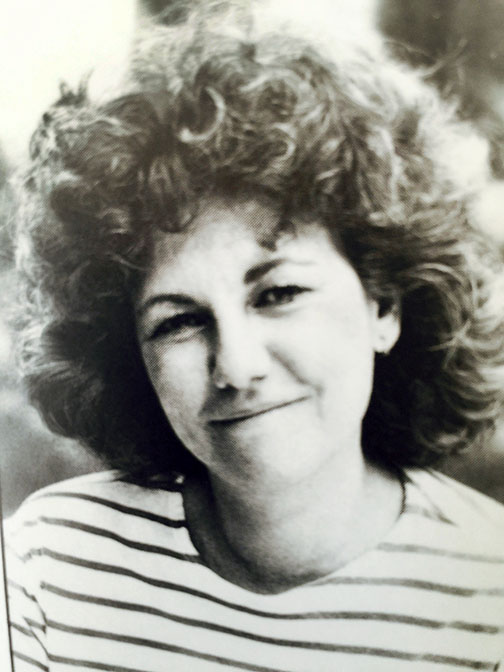

For many, Laurie Colwin became one of those favored writerly cooks one likes to keep near and dear on the bookshelf and in the kitchen. She was a novelist and short story writer who also wrote food columns for Gourmet magazine that were collected in two volumes. She died in 1992 at the young age of 48, but her work has a long-standing place on many a list of revered food writing.

For many, Laurie Colwin became one of those favored writerly cooks one likes to keep near and dear on the bookshelf and in the kitchen. She was a novelist and short story writer who also wrote food columns for Gourmet magazine that were collected in two volumes. She died in 1992 at the young age of 48, but her work has a long-standing place on many a list of revered food writing.

When I sat down to read Colwin’s “Home Cooking,†(1988) and “More Home Cooking: A Writer Returns to the Kitchen†(1992), I discovered why Colwin struck such a chord with so many. An East Coast urban writer with a decidedly different background than mine, Colwin’s dry humor, love of food and cooking, lack of pretension and spare but precise prose made me realize that, yes, eating and words can bridge any seeming lack of common ground. She is now one of my select food writing companions. I wish she was still around. Her words make you wish she was your friend. Her books, at least, give you a friend via the page.

Colwin was down-to-earth and truthful and funny. Her dry-witted confessionals shared as much about went wrong in the kitchen as went right. In chapters titled “Kitchen Horrors†and “Repulsive Dinners: A Memoir,†she recounts her own misguided attempts, including her effort to impress the man she would marry by baking him a stuffed red snapper without consulting any recipe: “…does love need a recipe? Does inspiration require instructions?†She described the end result: “When it finally emerged from the oven, this fish looked like Hieronyomous Bosch’s vision of hell, with nasty-looking things spilling out into a pallid-looking of undercooked fish juices.†You can trust such a writer who is willing to admit to her failings, but of course, those make the most humorous fodder for the page, as was her Christmas Eve serving of a Dundee Cake she described as “a ring of buttered sawdust in which was embedded a series of jujubes…â€

Her style — both in the kitchen and on the page — was one of economy. Her kitchen seemed a place that lacked fussiness, even in how it was equipped. In her essay, “The Low-Tech Person’s Batterie de Cuisine,†she wrote, “Most things are frills — few are essential. It is possible to cook well, with very little.†Her early days of cooking as a young adult were spent in a one-room apartment “a little larger than the Columbia Encyclopedia,†where, with a small metal counter, a toy-sized refrigerator, a two-burner stove equivalent of a hot plate and a bathroom sink, she still managed to entertain friends and cooked everything from toasted cheese, bean soups, pasta and eggplant.

Her style — both in the kitchen and on the page — was one of economy. Her kitchen seemed a place that lacked fussiness, even in how it was equipped. In her essay, “The Low-Tech Person’s Batterie de Cuisine,†she wrote, “Most things are frills — few are essential. It is possible to cook well, with very little.†Her early days of cooking as a young adult were spent in a one-room apartment “a little larger than the Columbia Encyclopedia,†where, with a small metal counter, a toy-sized refrigerator, a two-burner stove equivalent of a hot plate and a bathroom sink, she still managed to entertain friends and cooked everything from toasted cheese, bean soups, pasta and eggplant.

Colwin cooked for everyone — small gatherings in her home and even learned to cook for large groups, from feeding fellow college students homemade sandwiches to making shepherd’s pie for 100 when she was at the helm of a kitchen at a women’s shelter.

It was clear she cared deeply about what she served and to whom. She worked out menus for the fussy eaters she knew everyone must contend with, though she didn’t come through it unscathed: “For those who have problems sleeping, making up menus for this range of problematic eaters provides lively late-night entertainment. If you do not have insomnia, fussy eaters in your social orbit will give it to you.â€

In her years of cooking, she winnowed down clearly what she liked — and what she didn’t. In “How to Avoid Grilling,†she warned against the charcoal briquet method of cookery: “Grilling is like sunbathing. Everyone knows it is bad for you but no one ever stops doing it. Since I do not like the taste of lighter fluid, I do not have to worry that a grilled steak is the equivalent of seven hundred cigarettes.â€

What Colwin seemed to celebrate was simple cooking that filled the bill. She loved potato salad and lentils and beef stew and polenta and pasta and sauteed vegetables and potato pancakes. She revered comforting desserts like steamed chocolate pudding and fruit salad.

She believed in a good fried chicken and her method of doing it right (“Mine is the only right way, and on this subject I feel almost evangelicalâ€): “Fried chicken must have a crisp, deep (but not too deep) crust. It must be completely cooked yet juicy and tender. These requirements sound minimal, but achieving them requires technique.â€

In “Bread Baking Without Agony,†Colwin found a way to usurp the time shackles of kneading and raising, as her instructions liberate the home baker: “Knead the dough well, roll it in flour, put it in a warm bowl (although I have put it in a regular old bowl right off the shelf). Leave it in a cool draft-free place and go about your business. Whenever you happen to get home, punch down the dough, knead it well, roll it in flour and forget about it until convenient.â€

In “Bread Baking Without Agony,†Colwin found a way to usurp the time shackles of kneading and raising, as her instructions liberate the home baker: “Knead the dough well, roll it in flour, put it in a warm bowl (although I have put it in a regular old bowl right off the shelf). Leave it in a cool draft-free place and go about your business. Whenever you happen to get home, punch down the dough, knead it well, roll it in flour and forget about it until convenient.â€

Colwin’s writing is enough to savor on its own. Of her cooking,she was modest: “I am not a fancy cook or an ambitious one. I am just a plain old cook.†I found a number of her “plain old†recipes appealing. The recipe format in “Home Cooking†is decidedly informal, just sets of directions, as if a friend was telling you over the phone how to make this or that. She sold me on a creamed spinach recipe, and I was surprised to be so taken with it, but it had a comforting retro aspect to it. Also, Colwin claimed to have made it about 500 times and, by the time it was consumed at Colwin’s table and the recipe shared through friends of friends, eaten by “half the Western Hemisphere,†it was clear that it has been thoroughly road-tested.

Colwin’s writing is enough to savor on its own. Of her cooking,she was modest: “I am not a fancy cook or an ambitious one. I am just a plain old cook.†I found a number of her “plain old†recipes appealing. The recipe format in “Home Cooking†is decidedly informal, just sets of directions, as if a friend was telling you over the phone how to make this or that. She sold me on a creamed spinach recipe, and I was surprised to be so taken with it, but it had a comforting retro aspect to it. Also, Colwin claimed to have made it about 500 times and, by the time it was consumed at Colwin’s table and the recipe shared through friends of friends, eaten by “half the Western Hemisphere,†it was clear that it has been thoroughly road-tested.

I’ve never been much of a side dish whiz, but this one, I’d make again. It comes together simply with cooked frozen spinach, onion, garlic, evaporated milk, celery salt, Monterey Jack cheese and chopped jalapeno pepper (she recommends the pickled version).

I’ve never been much of a side dish whiz, but this one, I’d make again. It comes together simply with cooked frozen spinach, onion, garlic, evaporated milk, celery salt, Monterey Jack cheese and chopped jalapeno pepper (she recommends the pickled version).

Everything is cooked together on the stovetop, then poured into a buttered baking dish and topped with buttered bread crumbs.

The end dish is one you would be proud to set upon your Thanksgiving table among all the traditional sides. It is creamy and flavorful; rich yet surprisingly light. The jalapenos lend a little kick and marry beautifully with everything else.

Creamed Spinach with Jalapeno Peppers

From “Home Cooking: A Writer in the Kitchen†by Laurie Colwin (1988)

Serves 8

Cook two packages of frozen spinach. Drain, reserving one cup of liquid, and chop fine.

Melt four tablespoons of butter in a saucepan and add two tablespoons of flour. Blend and cook a little. Do not brown.

Add two tablespoons of chopped onion and one clove of minced garlic.

Add one cup of spinach liquid slowly, then add 1/2 cup of evaporated milk, some fresh black pepper, 3/4 teaspoon of celery salt, and six ounces of Monterey Jack cheese cut into cubes. Add one or more chopped jalapeno pepper (how many is a question of taste as well as what kind. I myself use the pickled kind, from a jar) and then the spinach. Cook until all is blended.

Turn into a buttered casserole, top with buttered bread crumbs and bake for about 45 minutes at 300 degrees.

[A]nother favorite of Colwin’s was gingerbread — REAL gingerbread of the baked-like-a-cake sort, which is also something old-fashioned. I think gingerbread used to be more on the dessert table year-round. While I had made gingerbread cookies, I had never made pan gingerbread except from mixes, which, as Colwin put it “are uniformly disgusting.â€

[A]nother favorite of Colwin’s was gingerbread — REAL gingerbread of the baked-like-a-cake sort, which is also something old-fashioned. I think gingerbread used to be more on the dessert table year-round. While I had made gingerbread cookies, I had never made pan gingerbread except from mixes, which, as Colwin put it “are uniformly disgusting.â€

Colwin wrote she made the gingerbread numerous times, often topping it with a chocolate icing or spreading it with jam. “Its spicy, embracing taste is the perfect thing for a winter afternoon,†she wrote. “When you serve it, once they have stopped giving you a funny look, people often say: ‘Gingerbread! I haven’t had that since I was a child.’â€

Colwin adapted her gingerbread recipe from “Charleston Receipts,†(1950) and recommends a Louisiana molasses called Steen’s Pure Ribbon Cane Syrup, which she ordered (as did I, from Amazon). “You do not need Steen’s to make gingerbread,†Colwin wrote, “but I see it as one of life’s greatest delights: a cheap luxury.â€

Colwin adapted her gingerbread recipe from “Charleston Receipts,†(1950) and recommends a Louisiana molasses called Steen’s Pure Ribbon Cane Syrup, which she ordered (as did I, from Amazon). “You do not need Steen’s to make gingerbread,†Colwin wrote, “but I see it as one of life’s greatest delights: a cheap luxury.â€

The cake is easy enough to whip up, filled with spices and brown sugar and buttermilk and spread humbly in a square cake pan (although Colwin baked the cake in various sizes, including her daughter’s toy cake tins). It fills the air with a warm comforting spice (like Colwin’s writing). This cake is so soft, tender and spicy. I made it a few times, topping it with powdered sugar, and in small cupcake form, a little cream cheese icing. Also, like Colwin’s work, it has a long shelf life: “It improves with age, should you be lucky or restrained enough to keep any around.â€

The cake is easy enough to whip up, filled with spices and brown sugar and buttermilk and spread humbly in a square cake pan (although Colwin baked the cake in various sizes, including her daughter’s toy cake tins). It fills the air with a warm comforting spice (like Colwin’s writing). This cake is so soft, tender and spicy. I made it a few times, topping it with powdered sugar, and in small cupcake form, a little cream cheese icing. Also, like Colwin’s work, it has a long shelf life: “It improves with age, should you be lucky or restrained enough to keep any around.â€

Gingerbread

From “Home Cooking: A Writer in the Kitchen†by Laurie Colwin (1988)

Makes one 9-inch cake

Cream one stick of sweet butter with 1/2 cup of light or dark brown sugar. Beat until fluffy and add 1/2 cup of molasses.

Beat in two eggs

Add 1 1/2 cups of flour, 1/2 teaspoon of baking soda and one very generous tablespoon of ground ginger (this can be adjusted to taste, but I like it very gingery). Add one teaspoon of cinnamon, 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves and 1/4 teaspoon of ground allspice.

Add two teaspoons of lemon brandy. If you don’t have any, use plain vanilla extract. Lemon extract will not do. Than add 1/2 cup of buttermilk (or milk with a little yogurt beaten into it) and turn batter into a buttered tin.

Bake at 350 degrees for between twenty and thirty minutes (check after twenty minutes have passed). Test with a broom straw, and cool on a rack.